On the short cool afternoons on our complex outside of Accra, we go up on the balcony, beverage in hand, and contemplate the sea.

Unfortunately the view isn't as good as it used to be, as there has been an explosion of building along the coast, especially hotels. In particular, hotels between us and the beach. So the picture above (taken last year) is not exactly current. But you can occasionally get a glimpse of the fishing boats returning in the afternoon between the block wall that now obscure our view.

Here's how it works. Around sunset, the fishing boats sail off and in the late morning--or possibly the afternoon, they return. The fishing is still pretty good near Accra if you go far enough offshore. The late upwelling has prolonged the good catches this year.

But fishing is meager in the eastern and central portions of Ghana. There used to be far more boats plying their trade than do now.

The artisanal fishery is of critical importance. Nearly 25% of Ghana's population lives in the coastal zone. Until the past decade, approximately 10% of the population depended on the fishery for their livelihood (Quaatey, 1996). It seems that that number has declined in recent years. I recall seeing estimates exceeding 30% for the amount of protein in the Ghanaian diet that came from the sea.

Climatic fluctuations over the past fifty years are reflected in the catches of artisanal fishermen (Minta, 2003), but it is not as clear whether the more or less monotonic decline in fish catches over the past decades can entirely be laid at the feet of climate change. Different species respond in different ways to climatic fluctuations--the most important being temperature, rainfall, and strength and duration of upwelling. But against climate change we need to consider the backdrop of changing technology in both the artisanal and mechanized fishing fleets.

In 1996, when I began work in coastal Ghana, I saw significant fishing fleets at many villages along the coast. In particular, the village of Nakwa, at the mouth of the Nakwa River, behind a lagoon fronted by an impressive sand barrier, had a large fishing fleet full of vessels at least sixty feet in length which landed on the barrier. The fishing boats were brightly painted and festooned with colourful banners. There were ferries constantly running across the lagoon between the village and the landing ground for the fishing fleet.

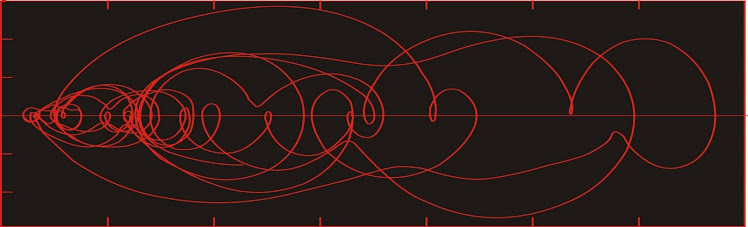

Two years ago I ran a sidescan sonar survey out of Nakwa between the river mouth and the offshore oil platform (GNPC-Saltpond). The fishing fleet was gone, but for a couple of dilapidated wrecks drawn up on shore. The locals told me there was no more fishing--anyone from the village who wanted to fish had to travel 150 km west to Axim, where the fishing was still good.

In 1997, in the course of offshore work near Axim, we encountered the artisanal fishing fleet several km offshore at night. The canoes all used lights to lure the fish in where they could be netted. At the time, this was the most technologically sophisticated method of artisanal fishing. Since then, new technologies have been deployed, including underwater lights and the use of chemicals.

The use of technology by the artisanal fishing industry varies from locality to locality. In the far west of Ghana, there has been an attempt to manage the fishery by limiting certain methods (CRC), but such efforts are nearly always local.

This year (so it has been reported), the fishing has ceased off Axim, and the fishermen have been forced further west to Cote d'Ivoire.

Overshadowing the increased efforts of the artisanal fishery is the steady increase in industrial fishing effort.

In 2010 I observed pair-trawling (which is illegal in most places). Sidescan surveys show that the seafloor is crossed by abundant trawl marks, even in nearshore areas that are supposed to be off-limits to such techniques. Trawling disturbs large areas of the seafloor, reducing marine productivity for years.

As the trawling has entered into the waters which were reserved for the artisanal fishermen, it is little surprise that the inshore fishery has suffered.

References

[CRC] Coastal Resources Center / Friends of the Nation (2011). Assessment of Critical Coastal Habitats of the Western Region, Ghana. Integrated Coastal and Fisheries Governance Initiative for the Western Region of Ghana. Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island,132 pages.

Minta, S. O., 2003. An assessment of the vulnerability of Ghana's coastal artisanal fishery to climate change. M. Sc. thesis, University of Tromso, Norway.

Quaatey, S. N. K., 1996. Report on the synthesis of recent evaluations undertaken on the major fish stock in Ghanaian waters. Marine Fisheries Research Division, Fisheries Directorate of the Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Tema, Ghana.

Unfortunately the view isn't as good as it used to be, as there has been an explosion of building along the coast, especially hotels. In particular, hotels between us and the beach. So the picture above (taken last year) is not exactly current. But you can occasionally get a glimpse of the fishing boats returning in the afternoon between the block wall that now obscure our view.

Here's how it works. Around sunset, the fishing boats sail off and in the late morning--or possibly the afternoon, they return. The fishing is still pretty good near Accra if you go far enough offshore. The late upwelling has prolonged the good catches this year.

But fishing is meager in the eastern and central portions of Ghana. There used to be far more boats plying their trade than do now.

The artisanal fishery is of critical importance. Nearly 25% of Ghana's population lives in the coastal zone. Until the past decade, approximately 10% of the population depended on the fishery for their livelihood (Quaatey, 1996). It seems that that number has declined in recent years. I recall seeing estimates exceeding 30% for the amount of protein in the Ghanaian diet that came from the sea.

Climatic fluctuations over the past fifty years are reflected in the catches of artisanal fishermen (Minta, 2003), but it is not as clear whether the more or less monotonic decline in fish catches over the past decades can entirely be laid at the feet of climate change. Different species respond in different ways to climatic fluctuations--the most important being temperature, rainfall, and strength and duration of upwelling. But against climate change we need to consider the backdrop of changing technology in both the artisanal and mechanized fishing fleets.

In 1996, when I began work in coastal Ghana, I saw significant fishing fleets at many villages along the coast. In particular, the village of Nakwa, at the mouth of the Nakwa River, behind a lagoon fronted by an impressive sand barrier, had a large fishing fleet full of vessels at least sixty feet in length which landed on the barrier. The fishing boats were brightly painted and festooned with colourful banners. There were ferries constantly running across the lagoon between the village and the landing ground for the fishing fleet.

Two years ago I ran a sidescan sonar survey out of Nakwa between the river mouth and the offshore oil platform (GNPC-Saltpond). The fishing fleet was gone, but for a couple of dilapidated wrecks drawn up on shore. The locals told me there was no more fishing--anyone from the village who wanted to fish had to travel 150 km west to Axim, where the fishing was still good.

Nakwa lagoon in 2010.

Flaring gas near Saltpond.

In 1997, in the course of offshore work near Axim, we encountered the artisanal fishing fleet several km offshore at night. The canoes all used lights to lure the fish in where they could be netted. At the time, this was the most technologically sophisticated method of artisanal fishing. Since then, new technologies have been deployed, including underwater lights and the use of chemicals.

The use of technology by the artisanal fishing industry varies from locality to locality. In the far west of Ghana, there has been an attempt to manage the fishery by limiting certain methods (CRC), but such efforts are nearly always local.

This year (so it has been reported), the fishing has ceased off Axim, and the fishermen have been forced further west to Cote d'Ivoire.

Overshadowing the increased efforts of the artisanal fishery is the steady increase in industrial fishing effort.

In 2010 I observed pair-trawling (which is illegal in most places). Sidescan surveys show that the seafloor is crossed by abundant trawl marks, even in nearshore areas that are supposed to be off-limits to such techniques. Trawling disturbs large areas of the seafloor, reducing marine productivity for years.

As the trawling has entered into the waters which were reserved for the artisanal fishermen, it is little surprise that the inshore fishery has suffered.

References

[CRC] Coastal Resources Center / Friends of the Nation (2011). Assessment of Critical Coastal Habitats of the Western Region, Ghana. Integrated Coastal and Fisheries Governance Initiative for the Western Region of Ghana. Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island,132 pages.

Minta, S. O., 2003. An assessment of the vulnerability of Ghana's coastal artisanal fishery to climate change. M. Sc. thesis, University of Tromso, Norway.

Quaatey, S. N. K., 1996. Report on the synthesis of recent evaluations undertaken on the major fish stock in Ghanaian waters. Marine Fisheries Research Division, Fisheries Directorate of the Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Tema, Ghana.

No comments:

Post a Comment