Bull markets need to rise the farthest with the rewest people on them. So if the gold market is to remain in a bull market, something has to be done to cool off the market.

These short sharp drops of $50 or so just aren't doing it anymore. The price and enthusiasm comes roaring back each time.

In the 1970s, during gold's run from $35 to $800, there was an 18-month interlude where the price was cut in half (from about $200 to $100). I've thought for a few years now that a similar correction has to occur sometime during this bull market in gold. Now, however, I think that the level of patience in the market in general is such that only half of such a correction is necessary--say 25% over nine months.

This could be achieved by a slow grind downward at a rate of $50 per month for nine months.

Can you imagine the mindset if the price of gold were $900 in nine months time? The gloating on financial TV. That would definitely look like the end of the bull market. And that is the perception that has to come.

Of course, it wouldn't be a straight grind downward. It would be punctuated by brief $50 to $100 rallies to suck speculators in repeatedly and destroy them. That's how you destroy speculators.

So if such a correction is coming (it may or may not be starting now) what is the plan?

First of all I never sell any physical metal. In previous selloffs I find you can never get it back at the lower price.

I am building cash in stock trading acccounts, but holding core positions. Just selling a little in to strength, and occasionally buy on weakness.

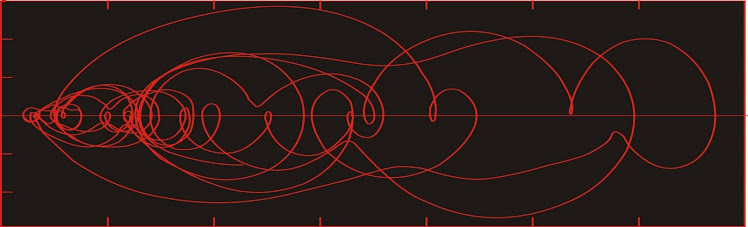

Dust flux, Vostok ice core

Two dimensional phase space reconstruction of dust flux from the Vostok core over the period 186-4 ka using the time derivative method. Dust flux on the x-axis, rate of change is on the y-axis. From Gipp (2001).

Friday, October 29, 2010

Monday, October 25, 2010

Ghanaians: The Beautiful People

Ghanaians are among the most beautiful people in the world. This is based on careful observation over several years.

Kwame visits a herbalist, Makola Market, Accra 2010.

Coffin-makers in Axim, 2002.

Bartender, Shama, 2008 (left). Electrician near Bortianor, 2010 (right).

Father and son, Central Region, 2007 (left). Egg-seller and children, Adabraka, 2010 (right).

Artisanal miner, Western Region, 1997 (left). Hotel staff, Axim, 2008 (right).

Market seller and daughter, Agbogbloshie, 1997 (left). Grasscutter vendor, Mankessim, 2007 (right).

Village elder, Kakum, 2007 (left). Women and child at block plant, Central Region, 2005 (right).

Visiting dignitaries at the funeral of the Asanta Chief, 2008.

Corn vendor, Awuna Beach Village, 2002.

Children returning from school in SCC-Mandela, 2007.

Workmen near Oshiye, 2010. They said I could take their picture but had to help them find wives.

Communal labour day in Axim, 1997.

Parade in Axim, 2002.

Looking at these pictures I see the majority of the people are Nzema (from the Western Region). Not to say these are the most beautiful in Ghana, just I spend most of my time there.

Sunday, October 24, 2010

What has made you rich has made you poor

Electricity has been at a premium since a fantastic lightning storm here in Accra ten nights ago damaged the local power grid. We have had electricity over only about 24 hours in the first five days. It's been better since.

Such things get me thinking about scarcity in general. The prices of many commodities have soared over the past two decades, particularly in the last ten years. What’s behind it?

Some have argued for “peak everything”.

Much has been written on the concept of peak oil. The idea here is that once we reach the point where we have produced about one-half of all oil in existence, oil production will decline. Some might argue we can keep production up awhile longer, but the idea is that as the amount remaining declines, eventually production must decline.

Hubbert said “We cannot produce what we have not discovered.”

The Earth is large, and for the most part we have barely scratched the surface. If the world were the size of a billiard ball, the depth to which we have plunged in search of resources would not even be visible. From my perspective as a geologist whose prime interest is in metals, we are nowhere near the peak ability to produce metals.

A paper published some years ago proposed the existence of a sphere of uranium (and other heavy metals) at the centre of the Earth, and some preliminary evidence that this sphere would have a radius of up to 6 km. Quite a lot of uranium, but I don’t care to hazard a guess as to the cost of its extraction*.

Oil, however, is a different matter. Given what we know of its formation, there cannot be substantial and increasing pools of accessible hydrocarbon at successively greater depths within the Earth beyond some level fairly close to the surface. Alternative theories of deep hot biospheres or primary hydrocarbon have extremely limited evidence in their favour, and in any case, the few molecules of hydrocarbon which may have been demonstrated to have drifted up through the basement geology from the deep Earth are but a small drop in the ocean of world demand. Oil is definitely a commodity which could be at or near its peak of production.

Having said that, I think we would find that at a price of about $1000/bbl (in constant 2010 dollars—no fair printing your way to this price!) we would still find a lot of oil at depth. But for geological reasons, this oil will be extremely expensive to discover and produce (hence the need for $1000/bbl).

The deeper the rocks are, the more tectonic episodes they have experienced. An oil reservoir is very simply the volume contained within a fold in the rocks. The deeper you go, the more complex the folding, and the smaller the individual volumes. You have two technical challenges, leading to greatly increased costs—first, the targets are small, so they are difficult to “image” using geophysical techniques, and difficult to hit with a drill; and second, the reservoir is small, so there is not much economic benefit to offset the much higher costs (except by a much higher price).

Beyond this depth, you don’t have much chance of finding anything at all, as the temperature is too high to preserve the most valuable hydrocarbons.

Most of the data we have collected to date in the search for oil (and there are reams of it—I once heard that a major oil company was prepared to donate its entire collection of eastern Canada seismic data to the Geological Survey—just the tapes alone would fill a small building) are useless for looking for these deeper, smaller structures. It hurts to admit it, but there it is.

There is a small problem called spatial aliasing. You have a complex curve as in the figure. But your sampling is limited. How you sample is called CDP stacking. A series of shots are set off and the results recorded on geophones, and simply, all the reflections occur off one common point at depth, which is the sampled point. Then the entire array is dragged along some distance and repeated. But the smallest target that can be resolved is a function of your sampling interval. In particular, you need two samples to define a bend in the rocks (defining it accurately requires more).

If exploration geophysicists had unlimited budgets and placed no value on time, I have no doubt they would sample more frequently. But budgets are limited, and so geophysicists collect the minimum amount of data necessary to define their targets of interest, which over the past couple of decades have been that second layer of hydrocarbons in my cartoon of oil distribution. This data is not nearly dense enough to resolve the smaller targets on the third layer above.

What happens when you try to interpret geology without adequate data?

Oh yeah--you have to click on this figure for it to do anything.

Holy crap! Those hundred-million dollar holes that were supposed to be into a fat juicy anticline went into nothing! Not only are you fired and blacklisted from the industry, but you and your extended family are hereby sold into slavery.

So let’s leave aside oil for a moment.

What about metals? If we are nowhere near their peak production, why have their prices risen so sharply?

One reason may be inflation. More dollars chasing the metals.

There could be another—and that has to do with the fall of the price of metals (and most commodities) that began in the early 1970s. This fall had more to do with the rise of commodity futures trading than it did a sudden per capita increase in metals production. Many charts showed a drop in per capita production of basic commodities.

The per capita production of copper has risen through the 20th century, but four declines are apparent--WWI, the Depression, WWII, and the period from 1975 to 1985 or 90. Other commodity graphs appear similar. Was there an economic implosion equal to a Great Depression or a World War in that period?

When I was teaching early in the last decade, it was fashionable to look at such graphs and wonder if production for many of these metals was peaking.

The real reason for the drop in per capita production has to do with the fall in price. For producers, price is a signal. A rising price tells you to increase production. A falling price tells you to reduce production.

The problem comes from the paper pushers. If you have a certain amount of wealth, it seems intuitively obvious that if the price of what you have to buy falls, then you become wealthier. But this is only true if price falls due to an increase in supply.

If the price has fallen because of the ability of large corporate and banking interests to control the price downwards through the issuance of paper, then your wealth is not actually increasing.

After all, what is wealth? Isn’t wealth actually stuff—gold, oil, copper, grain, meat? If you drive the price down, but at the same time you have less stuff, then you have become poorer—for wealth is an abundance of oil, of gold, of food; but not of paper (or its electronic equivalents).

Creating all this paper has not made us richer! It has made us poorer!

Notice how per capita production of copper has increased over the past fifteen years. Do you feel richer? You should . . . except that much of that extra copper has gone to China, so unless you have been Chinese over that interval, you are not much wealthier (much like how the rapid growth from 1950 to 1975 was mainly experienced in North America).

We are a long way from the peak of everything (oil being the probable exception). We are currently in the process of revaluing real commodities in terms of paper. This revaluation is the equivalent of a complex system leaping from one metastable state to another. Huge volatility lies in our future, as corporate and banking interests, backed by huge government bailouts, double and redouble their efforts to regain control of commodity prices.

*The cheapest way to extract it may be to blow up the Earth. But there is an easy way to protect yourself. You simply buy land futures and take delivery after the Earth is destroyed!

Blogging by battery. Unfortunately I blew up the inverter last night.

Such things get me thinking about scarcity in general. The prices of many commodities have soared over the past two decades, particularly in the last ten years. What’s behind it?

Some have argued for “peak everything”.

Much has been written on the concept of peak oil. The idea here is that once we reach the point where we have produced about one-half of all oil in existence, oil production will decline. Some might argue we can keep production up awhile longer, but the idea is that as the amount remaining declines, eventually production must decline.

Hubbert said “We cannot produce what we have not discovered.”

The Earth is large, and for the most part we have barely scratched the surface. If the world were the size of a billiard ball, the depth to which we have plunged in search of resources would not even be visible. From my perspective as a geologist whose prime interest is in metals, we are nowhere near the peak ability to produce metals.

A paper published some years ago proposed the existence of a sphere of uranium (and other heavy metals) at the centre of the Earth, and some preliminary evidence that this sphere would have a radius of up to 6 km. Quite a lot of uranium, but I don’t care to hazard a guess as to the cost of its extraction*.

Oil, however, is a different matter. Given what we know of its formation, there cannot be substantial and increasing pools of accessible hydrocarbon at successively greater depths within the Earth beyond some level fairly close to the surface. Alternative theories of deep hot biospheres or primary hydrocarbon have extremely limited evidence in their favour, and in any case, the few molecules of hydrocarbon which may have been demonstrated to have drifted up through the basement geology from the deep Earth are but a small drop in the ocean of world demand. Oil is definitely a commodity which could be at or near its peak of production.

Having said that, I think we would find that at a price of about $1000/bbl (in constant 2010 dollars—no fair printing your way to this price!) we would still find a lot of oil at depth. But for geological reasons, this oil will be extremely expensive to discover and produce (hence the need for $1000/bbl).

The deeper the rocks are, the more tectonic episodes they have experienced. An oil reservoir is very simply the volume contained within a fold in the rocks. The deeper you go, the more complex the folding, and the smaller the individual volumes. You have two technical challenges, leading to greatly increased costs—first, the targets are small, so they are difficult to “image” using geophysical techniques, and difficult to hit with a drill; and second, the reservoir is small, so there is not much economic benefit to offset the much higher costs (except by a much higher price).

Beyond this depth, you don’t have much chance of finding anything at all, as the temperature is too high to preserve the most valuable hydrocarbons.

Most of the data we have collected to date in the search for oil (and there are reams of it—I once heard that a major oil company was prepared to donate its entire collection of eastern Canada seismic data to the Geological Survey—just the tapes alone would fill a small building) are useless for looking for these deeper, smaller structures. It hurts to admit it, but there it is.

There is a small problem called spatial aliasing. You have a complex curve as in the figure. But your sampling is limited. How you sample is called CDP stacking. A series of shots are set off and the results recorded on geophones, and simply, all the reflections occur off one common point at depth, which is the sampled point. Then the entire array is dragged along some distance and repeated. But the smallest target that can be resolved is a function of your sampling interval. In particular, you need two samples to define a bend in the rocks (defining it accurately requires more).

If exploration geophysicists had unlimited budgets and placed no value on time, I have no doubt they would sample more frequently. But budgets are limited, and so geophysicists collect the minimum amount of data necessary to define their targets of interest, which over the past couple of decades have been that second layer of hydrocarbons in my cartoon of oil distribution. This data is not nearly dense enough to resolve the smaller targets on the third layer above.

What happens when you try to interpret geology without adequate data?

Oh yeah--you have to click on this figure for it to do anything.

Holy crap! Those hundred-million dollar holes that were supposed to be into a fat juicy anticline went into nothing! Not only are you fired and blacklisted from the industry, but you and your extended family are hereby sold into slavery.

So let’s leave aside oil for a moment.

What about metals? If we are nowhere near their peak production, why have their prices risen so sharply?

One reason may be inflation. More dollars chasing the metals.

There could be another—and that has to do with the fall of the price of metals (and most commodities) that began in the early 1970s. This fall had more to do with the rise of commodity futures trading than it did a sudden per capita increase in metals production. Many charts showed a drop in per capita production of basic commodities.

Global copper production in tonnes per thousand population. Data compiled from

USGS and UN 2004 projections, digitized at five year intervals.

The per capita production of copper has risen through the 20th century, but four declines are apparent--WWI, the Depression, WWII, and the period from 1975 to 1985 or 90. Other commodity graphs appear similar. Was there an economic implosion equal to a Great Depression or a World War in that period?

When I was teaching early in the last decade, it was fashionable to look at such graphs and wonder if production for many of these metals was peaking.

The real reason for the drop in per capita production has to do with the fall in price. For producers, price is a signal. A rising price tells you to increase production. A falling price tells you to reduce production.

The problem comes from the paper pushers. If you have a certain amount of wealth, it seems intuitively obvious that if the price of what you have to buy falls, then you become wealthier. But this is only true if price falls due to an increase in supply.

If the price has fallen because of the ability of large corporate and banking interests to control the price downwards through the issuance of paper, then your wealth is not actually increasing.

After all, what is wealth? Isn’t wealth actually stuff—gold, oil, copper, grain, meat? If you drive the price down, but at the same time you have less stuff, then you have become poorer—for wealth is an abundance of oil, of gold, of food; but not of paper (or its electronic equivalents).

Creating all this paper has not made us richer! It has made us poorer!

Notice how per capita production of copper has increased over the past fifteen years. Do you feel richer? You should . . . except that much of that extra copper has gone to China, so unless you have been Chinese over that interval, you are not much wealthier (much like how the rapid growth from 1950 to 1975 was mainly experienced in North America).

We are a long way from the peak of everything (oil being the probable exception). We are currently in the process of revaluing real commodities in terms of paper. This revaluation is the equivalent of a complex system leaping from one metastable state to another. Huge volatility lies in our future, as corporate and banking interests, backed by huge government bailouts, double and redouble their efforts to regain control of commodity prices.

*The cheapest way to extract it may be to blow up the Earth. But there is an easy way to protect yourself. You simply buy land futures and take delivery after the Earth is destroyed!

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

Bifurcation to come in our economic decline?

I have been trying to finish this entry forever, but power has been out here for almost three days now due to an electrical storm a few nights ago. I have been running off portable batteries, charging once in awhile when we run the generator.

One debate I seem to have over and over again with one of my fellow expats here in Ghana is the success (or lack thereof) of central banks in controlling the unfolding economic decline.

This friend of mine insists that central banks will do what they have always done, which is oversee a gradual decline of economic power in the West, while ensuring enough volatility that it is hard for someone to sit in a long (or short) position and profit all the way down.

My thinking is informed by the behaviour I have observed in dynamic systems. Systems behave simply and change slowly over more than 99.9% of observable time, but behave unpredictably and change very rapidly during the remaining <0.1% of observable time.

The behaviour of dynamic systems, like climate, is nearly linear much of the time, but is characterized by episodic reorganizations. These reorganizations resemble car accidents, in that your life afterwards may have no similarity to your life beforehand. Consequently, trying to predict the behaviour of a system after a bifurcation is as difficult as predicting you will be in a car accident next week.

About all we can do is anticipate when the bifurcation will take place.

Central banks normally try to hide what they are doing, because they don't want the general population protecting themselves against the consequences of their actions. If you need deflation, you also need the general population to be hurt by it, otherwise there is no benefit. However this requires a prediction of what the general populace is going to do, and I think that this will prove the weak point of central bank operations.

For instance, the future operation of the system may well depend on people continuing to make their mortgage payments, even if the value of the house has fallen below the amount owing. Between the holy hell of MERS and all the recent foreclosure failings, it seems likely that more and more people are going to give up on those mortgage payments.

Whenever the central bank tries to interfere with the workings of the economy in order to bring about a desired change, the general population is going to have to act in the manner predicted by the genius economic modelers at these banks. But modeling is really hard, in this case because the behaviour of the population is unpredictable.

Here is an example. Some years ago the Canadian Mint introduced a one-dollar coin with a picture of a loon. The coin was made of nickel. The official opinion expressed was that Canadians would love these things and would call them “dollar coins” or “dollars”. But even before the coin was released, Canadians began calling them “loonies”, a name which has lasted to the present day.

A few years later, the Mint decided to introduce a two-dollar coin. This coin depicted a polar bear (now two polar bears). Once again, there was an official opinion—the public would call this coin the “Bear”. Of course, they were almost immediately known as “toonies”.

So much for the official prediction of public behaviour.

When the tipping point comes—and it likely won’t be recognized until afterwards—the changes will be broad and deep. I don’t know what our new world will be like. But I would guess it would have a lot less government and the economy would be more focussed on actual production and real wealth creation rather than the growth of paper assets.

One debate I seem to have over and over again with one of my fellow expats here in Ghana is the success (or lack thereof) of central banks in controlling the unfolding economic decline.

This friend of mine insists that central banks will do what they have always done, which is oversee a gradual decline of economic power in the West, while ensuring enough volatility that it is hard for someone to sit in a long (or short) position and profit all the way down.

My thinking is informed by the behaviour I have observed in dynamic systems. Systems behave simply and change slowly over more than 99.9% of observable time, but behave unpredictably and change very rapidly during the remaining <0.1% of observable time.

The behaviour of dynamic systems, like climate, is nearly linear much of the time, but is characterized by episodic reorganizations. These reorganizations resemble car accidents, in that your life afterwards may have no similarity to your life beforehand. Consequently, trying to predict the behaviour of a system after a bifurcation is as difficult as predicting you will be in a car accident next week.

About all we can do is anticipate when the bifurcation will take place.

Central banks normally try to hide what they are doing, because they don't want the general population protecting themselves against the consequences of their actions. If you need deflation, you also need the general population to be hurt by it, otherwise there is no benefit. However this requires a prediction of what the general populace is going to do, and I think that this will prove the weak point of central bank operations.

For instance, the future operation of the system may well depend on people continuing to make their mortgage payments, even if the value of the house has fallen below the amount owing. Between the holy hell of MERS and all the recent foreclosure failings, it seems likely that more and more people are going to give up on those mortgage payments.

Whenever the central bank tries to interfere with the workings of the economy in order to bring about a desired change, the general population is going to have to act in the manner predicted by the genius economic modelers at these banks. But modeling is really hard, in this case because the behaviour of the population is unpredictable.

Here is an example. Some years ago the Canadian Mint introduced a one-dollar coin with a picture of a loon. The coin was made of nickel. The official opinion expressed was that Canadians would love these things and would call them “dollar coins” or “dollars”. But even before the coin was released, Canadians began calling them “loonies”, a name which has lasted to the present day.

A few years later, the Mint decided to introduce a two-dollar coin. This coin depicted a polar bear (now two polar bears). Once again, there was an official opinion—the public would call this coin the “Bear”. Of course, they were almost immediately known as “toonies”.

So much for the official prediction of public behaviour.

When the tipping point comes—and it likely won’t be recognized until afterwards—the changes will be broad and deep. I don’t know what our new world will be like. But I would guess it would have a lot less government and the economy would be more focussed on actual production and real wealth creation rather than the growth of paper assets.

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

Monetary debasement and Canadian coins

As the value of money has declined over the past several years due to government mismanagement of the economy, the price of commodities has similarly risen. As a result, the metal content of numerous coins in the late 1990's greatly exceeded the face value of the coins.

In particular, Canadian nickels (pre-1982), each contain 1/100 of a pound of nickel and are worth about 10 cents each (metal content), but were as high as 27 cents a couple of years ago.

Canadian pennies were made out of copper until 1996, and are worth more than face value.

In 2007, the Canadian Mint began its Alloy Recovery Program, by which it removed old circulating coins and melted them down for the metal content, replacing them by clad steel coins, which are nearly worthless.

The problem I have with this is that coins are traditionally the only way the general populace has to protect itself against financial mismanagement by government. As coins were gradually debased, far-seeing individuals would hoard valuable coins (normally gold or silver) and only spend the debased coins.

But the Canadian government has jumped the gun, and is pre-empting the Canadian citizen. Poor Canadians no longer have any reasonable way to protect themselves from inflation, except by waking up and buying gold or silver. Luckily for the Canadian government, most Canadians are asleep at the switch. If they were to wake up in large numbers and start hoarding copper and nickel coins (still lots of pennies and nickels, though the dimes and quarters are effectively gone), the government's plan would fail.

In particular, Canadian nickels (pre-1982), each contain 1/100 of a pound of nickel and are worth about 10 cents each (metal content), but were as high as 27 cents a couple of years ago.

Canadian pennies were made out of copper until 1996, and are worth more than face value.

In 2007, the Canadian Mint began its Alloy Recovery Program, by which it removed old circulating coins and melted them down for the metal content, replacing them by clad steel coins, which are nearly worthless.

The problem I have with this is that coins are traditionally the only way the general populace has to protect itself against financial mismanagement by government. As coins were gradually debased, far-seeing individuals would hoard valuable coins (normally gold or silver) and only spend the debased coins.

But the Canadian government has jumped the gun, and is pre-empting the Canadian citizen. Poor Canadians no longer have any reasonable way to protect themselves from inflation, except by waking up and buying gold or silver. Luckily for the Canadian government, most Canadians are asleep at the switch. If they were to wake up in large numbers and start hoarding copper and nickel coins (still lots of pennies and nickels, though the dimes and quarters are effectively gone), the government's plan would fail.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)