In a recent paper, authors J. Müller and H. E. Frimmel discuss cycles in historic gold production and implications for the future of the monetary metal. The World Complex applauds such studies, especially when they are backed up by data. Even better that this is one is published on an open source, so anyone can view it.

The analyses used by the authors are reflective of Hubbert's (1982) approach to estimating future production on the basis of past production, however as we will see I take exception to some of the authors' conclusions. Let's go!

The authors' observations can be summarized as follows:

1) Gold production has grown at a rate of about 2% per year since about 1850.

2) Historic gold production has been strongly influenced by four cycles of discovery and exploitation

3) Exploited ore grades have declined steadily through time

4) The dollar value of gold discovered per dollar spent on exploration has fallen catastrophically since the 1960s.

Just to interject some comments on these observations--other authors have noted that this last exploration cycle has yielded less "bang for the buck" than others. But the data source is unclear--what do we mean by gold in the ground? Are these inferred resources? Defined reserves? Or gold actually mined? It may be that the poor performance of the last decade has to do with the regulatory expense of defining resources. And if the numbers above relate to mining, there are a lot of potential mines discovered in the past decade that are not yet in production.

Additionally, although gold production has been falling, according to USGS figures, world production increased in 2009 over 2008, although it is still short of 2001 production.

From these observations, the authors conclude:

1) Gold production will continue to decline, possibly until 2026.

2) Peak gold production may have been in 2001.

3) The total mineable gold in the earth's crust is estimated to be about 300,000 tonnes, approximately double the total mined historically.

Although it is true that you cannot produce what you have not discovered--we should be sure we understand why we haven't discovered it yet.

The authors point out that there are rather large errors at the historical beginning of the above graph (that would be at the left). Yet they use that segment of the graph to project total historical production (the "optimistic assessment".

Alternatively, they use a projection of the falling production of the last decade to estimate total production (the "pessimistic assessment"). However, when we go back to the top figure, we see that historical production has driven by major cycles. During these cycles there are periods of sharply rising production followed by declining production. Yet long-term production has increased. Therefore using the decline of the latest cycle ignores the possibility of future cycles (perhaps driven by the current re-exploration of previously mined out areas now possible due to improved recovery) and possible reversion to the historical mean rate of production growth--not indefinitely, but for some period of time.

One factor that seems to be missing in the authors' reasoning on gold production cycles is the cycle of investment. Although they correctly recognize a significant lag between peaks of production and peaks in price, reflecting the time required to prove up and build a mine. I would argue that the peak in mining production in 2001 is the lagged response to the price peak in 1979; and that the peak in production as a consequence of the ongoing rise in the price of gold will not be seen for some years.

That lag has increased of late, largely due to increased costs. Many of these costs are forecast to increase. But a large part of those costs are regulatory--and as the economy shifts from a financial basis back to real production of real things--we may find those regulatory costs falling.

I think that Hubbert's approach was driven by his familiarity with the oil market. I agree that like oil, there is only a finite amount of gold on earth; however the geological differences are sufficient that gold (and the other metals) may not lend themselves so easily to his method of analysis. I have written on this topic before: the appearance of peak production in metals may be simply due to lack of investment driven by the low prices of the last two decades.

It is true that mined gold grades are declining, and costs per ounce of gold mined are increasing. But this is true of all other metals mined through history. Human ingenuity ensures that gold will continue to be mined at lower and lower grades--although how low we can go over what timeframe cannot be foreseen.

Energy costs, in particular are expected to increase. But lack of energy by itself will not cause gold production to cease. Gold has the highest marginal utility. Production of gold will cease as we near the point where it requires more energy and materials to mine than can be paid for by an equivalent amount of gold.

It is nice to see an article of this type in a formal setting because in my experiences at both academic (AGU, GAC) and industry (PDAC) conferences, few geologists understand why anyone would wish to mine gold. It is interesting to ponder deep questions of the market.

For instance, if we take the USGS data and plot the apparent consumption (within the US) against price since 1900, we get the following:

How do we reconcile the above with classical ideas of supply and demand?

There are actually two separate hyperbolae in our demand-price graph.

The smaller hyperbola at left reflects price and demand prior to the expansion of the South African production (gold production cycle 3). The greater hyperbola reflects the ability of the American public to own gold.

An interesting feature is highlighted by the green ellipse--demand increasing along with price in years 2008 and 2009. Since the economic crisis which came into focus in 2008, it appears that gold may be acting as a Giffen good. It has been hypothesized that safe financial assets act as such during bad economic times, as evidenced by the recent price rises in both gold and bonds.

Update:

After corresponding with the lead author of the paper, he sent me a copy of a newer paper which contains a more favourable estimate of the global endowment of gold which may be eventually recovered by mining. In the new paper (Müller and Frimmel, 2011), the total mineable gold is estimated to be as high as 390,000 t; although with the caveat that the estimate is sensitive to the estimate of the amount of gold mined prior to 1900.

I still believe there are two points of contention.

1) It is easy to underestimate the amount of gold produced in Graeco-Roman times (and, indeed, by the Incas), but the amount may have been substantial. As support I offer the following:

Gold has been of considerable significance for thousands of years. Apart from the busy-ness of Mediterranean cultures, a great deal of gold migrated from West Africa to Europe in historical times.

As for the peak in lead in the above chart, that is due to the removal of tetraethyl lead from gasoline in the 1970s. One last bit of deliciousness from the mid-20th century:

2) There is still another very large untapped frontier in gold exploration and mining--the seafloor. In addition to placer deposits on continental shelves, the work attempted by Nautilus Minerals Inc. near Papua New Guinea and Diamond Fields International in the Red Sea may prove ultimately to be game-changers. Last time I checked there was more sea than land, and if rift margins turn out to be the principal prospects for hydrothermal reasons, there are about five million square kilometres of highly prospective turf out there.

For disclosure--I do not work for and never have worked for either of the above companies, nor do I hold any position in shares, long or short, in either of them.

References:

Delmas, R. J. and Legrand, M., 1998. Trends recorded in Greenland in relation with Northern Hemisphere anthropogenic pollution. IGACtivities, Issue 14.

Hubbert, M. K., 1982. Techniques of prediction as applied to oil and gas. U.S. Department of Commerce. NBS Special Publication 631, pp. 16-141.

Müller, J. and Frimmel, H. E., 2010. Numerical analysis of historic gold production cycles and implications for future subcycles. Open Geology Journal, v. 4, pp. 35-40.

Müller, J. and Frimmel, H. E., 2011. Abscissa-transforming second-order polynomial functions to approximate the unknown historic production of non-renewable resources. Mathematical Geosciences, doi: 10.1007/s11004-011-9351-8.

The analyses used by the authors are reflective of Hubbert's (1982) approach to estimating future production on the basis of past production, however as we will see I take exception to some of the authors' conclusions. Let's go!

The authors' observations can be summarized as follows:

1) Gold production has grown at a rate of about 2% per year since about 1850.

2) Historic gold production has been strongly influenced by four cycles of discovery and exploitation

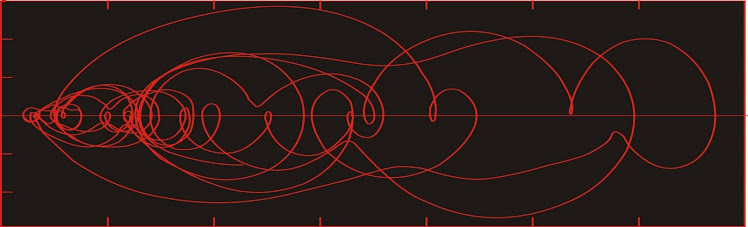

Exponential curve fitted to gold production--four cycles highlighted.

No doubt the first hiccup at about 1850 is California, and the little peak

before the first cycle is the Yukon. From Müller and Frimmel (2010).

3) Exploited ore grades have declined steadily through time

4) The dollar value of gold discovered per dollar spent on exploration has fallen catastrophically since the 1960s.

Discovered gold per dollar of exploration expenditure. From Müller and Frimmel (2010).

Just to interject some comments on these observations--other authors have noted that this last exploration cycle has yielded less "bang for the buck" than others. But the data source is unclear--what do we mean by gold in the ground? Are these inferred resources? Defined reserves? Or gold actually mined? It may be that the poor performance of the last decade has to do with the regulatory expense of defining resources. And if the numbers above relate to mining, there are a lot of potential mines discovered in the past decade that are not yet in production.

Additionally, although gold production has been falling, according to USGS figures, world production increased in 2009 over 2008, although it is still short of 2001 production.

From these observations, the authors conclude:

1) Gold production will continue to decline, possibly until 2026.

2) Peak gold production may have been in 2001.

3) The total mineable gold in the earth's crust is estimated to be about 300,000 tonnes, approximately double the total mined historically.

Hubbert linearization graph projecting total production of gold to be between

230,000 and 280,000 tonnes of gold. Chartists might want to try

drawing your own lines. From Müller and Frimmel (2010).

Although it is true that you cannot produce what you have not discovered--we should be sure we understand why we haven't discovered it yet.

The authors point out that there are rather large errors at the historical beginning of the above graph (that would be at the left). Yet they use that segment of the graph to project total historical production (the "optimistic assessment".

Alternatively, they use a projection of the falling production of the last decade to estimate total production (the "pessimistic assessment"). However, when we go back to the top figure, we see that historical production has driven by major cycles. During these cycles there are periods of sharply rising production followed by declining production. Yet long-term production has increased. Therefore using the decline of the latest cycle ignores the possibility of future cycles (perhaps driven by the current re-exploration of previously mined out areas now possible due to improved recovery) and possible reversion to the historical mean rate of production growth--not indefinitely, but for some period of time.

One factor that seems to be missing in the authors' reasoning on gold production cycles is the cycle of investment. Although they correctly recognize a significant lag between peaks of production and peaks in price, reflecting the time required to prove up and build a mine. I would argue that the peak in mining production in 2001 is the lagged response to the price peak in 1979; and that the peak in production as a consequence of the ongoing rise in the price of gold will not be seen for some years.

That lag has increased of late, largely due to increased costs. Many of these costs are forecast to increase. But a large part of those costs are regulatory--and as the economy shifts from a financial basis back to real production of real things--we may find those regulatory costs falling.

I think that Hubbert's approach was driven by his familiarity with the oil market. I agree that like oil, there is only a finite amount of gold on earth; however the geological differences are sufficient that gold (and the other metals) may not lend themselves so easily to his method of analysis. I have written on this topic before: the appearance of peak production in metals may be simply due to lack of investment driven by the low prices of the last two decades.

It is true that mined gold grades are declining, and costs per ounce of gold mined are increasing. But this is true of all other metals mined through history. Human ingenuity ensures that gold will continue to be mined at lower and lower grades--although how low we can go over what timeframe cannot be foreseen.

Energy costs, in particular are expected to increase. But lack of energy by itself will not cause gold production to cease. Gold has the highest marginal utility. Production of gold will cease as we near the point where it requires more energy and materials to mine than can be paid for by an equivalent amount of gold.

It is nice to see an article of this type in a formal setting because in my experiences at both academic (AGU, GAC) and industry (PDAC) conferences, few geologists understand why anyone would wish to mine gold. It is interesting to ponder deep questions of the market.

For instance, if we take the USGS data and plot the apparent consumption (within the US) against price since 1900, we get the following:

How do we reconcile the above with classical ideas of supply and demand?

Normal demand varies inversely with price (red curves).

There are actually two separate hyperbolae in our demand-price graph.

The smaller hyperbola at left reflects price and demand prior to the expansion of the South African production (gold production cycle 3). The greater hyperbola reflects the ability of the American public to own gold.

An interesting feature is highlighted by the green ellipse--demand increasing along with price in years 2008 and 2009. Since the economic crisis which came into focus in 2008, it appears that gold may be acting as a Giffen good. It has been hypothesized that safe financial assets act as such during bad economic times, as evidenced by the recent price rises in both gold and bonds.

Update:

After corresponding with the lead author of the paper, he sent me a copy of a newer paper which contains a more favourable estimate of the global endowment of gold which may be eventually recovered by mining. In the new paper (Müller and Frimmel, 2011), the total mineable gold is estimated to be as high as 390,000 t; although with the caveat that the estimate is sensitive to the estimate of the amount of gold mined prior to 1900.

I still believe there are two points of contention.

1) It is easy to underestimate the amount of gold produced in Graeco-Roman times (and, indeed, by the Incas), but the amount may have been substantial. As support I offer the following:

Atmospheric lead in Greenland ice. Time runs right to left--note log scale.

The red ellipse shows the influence of Roman industry and mining, peaking

2,000 years ago, at levels which were not surpassed until the late 13th century.

The peak 20,000 years ago relates to glaciation. From Delmas and Legrand (1998).

Gold has been of considerable significance for thousands of years. Apart from the busy-ness of Mediterranean cultures, a great deal of gold migrated from West Africa to Europe in historical times.

As for the peak in lead in the above chart, that is due to the removal of tetraethyl lead from gasoline in the 1970s. One last bit of deliciousness from the mid-20th century:

I love the wholesome imagery. Lead--it's just like vitamins! Ladies Home Journal says so!

For disclosure--I do not work for and never have worked for either of the above companies, nor do I hold any position in shares, long or short, in either of them.

References:

Delmas, R. J. and Legrand, M., 1998. Trends recorded in Greenland in relation with Northern Hemisphere anthropogenic pollution. IGACtivities, Issue 14.

Hubbert, M. K., 1982. Techniques of prediction as applied to oil and gas. U.S. Department of Commerce. NBS Special Publication 631, pp. 16-141.

Müller, J. and Frimmel, H. E., 2010. Numerical analysis of historic gold production cycles and implications for future subcycles. Open Geology Journal, v. 4, pp. 35-40.

Müller, J. and Frimmel, H. E., 2011. Abscissa-transforming second-order polynomial functions to approximate the unknown historic production of non-renewable resources. Mathematical Geosciences, doi: 10.1007/s11004-011-9351-8.

Excellent analysis

ReplyDeleteIf I may quibble, if you read "To a question about the ancient man made lead

ReplyDeletein layers Greenland ice" by AM Tyurin, Candidate of Geological and Mineralogical Sciences, Vung Tau, Vietnam, available at http://new.chronologia.org/volume4/turin_sv.html

He shows that Pb correlates well with volcanic eruptions through time, and the peak 2000 years ago was not Romans poisoning the environment, nor was the rise since then due to lead in gasoline, although I think the great height that rise eventually got to may have been.