Electricity has been at a premium since a fantastic lightning storm here in Accra ten nights ago damaged the local power grid. We have had electricity over only about 24 hours in the first five days. It's been better since.

Such things get me thinking about scarcity in general. The prices of many commodities have soared over the past two decades, particularly in the last ten years. What’s behind it?

Some have argued for “peak everything”.

Much has been written on the concept of peak oil. The idea here is that once we reach the point where we have produced about one-half of all oil in existence, oil production will decline. Some might argue we can keep production up awhile longer, but the idea is that as the amount remaining declines, eventually production must decline.

Hubbert said “We cannot produce what we have not discovered.”

The Earth is large, and for the most part we have barely scratched the surface. If the world were the size of a billiard ball, the depth to which we have plunged in search of resources would not even be visible. From my perspective as a geologist whose prime interest is in metals, we are nowhere near the peak ability to produce metals.

A paper published some years ago proposed the existence of a sphere of uranium (and other heavy metals) at the centre of the Earth, and some preliminary evidence that this sphere would have a radius of up to 6 km. Quite a lot of uranium, but I don’t care to hazard a guess as to the cost of its extraction*.

Oil, however, is a different matter. Given what we know of its formation, there cannot be substantial and increasing pools of accessible hydrocarbon at successively greater depths within the Earth beyond some level fairly close to the surface. Alternative theories of deep hot biospheres or primary hydrocarbon have extremely limited evidence in their favour, and in any case, the few molecules of hydrocarbon which may have been demonstrated to have drifted up through the basement geology from the deep Earth are but a small drop in the ocean of world demand. Oil is definitely a commodity which could be at or near its peak of production.

Having said that, I think we would find that at a price of about $1000/bbl (in constant 2010 dollars—no fair printing your way to this price!) we would still find a lot of oil at depth. But for geological reasons, this oil will be extremely expensive to discover and produce (hence the need for $1000/bbl).

The deeper the rocks are, the more tectonic episodes they have experienced. An oil reservoir is very simply the volume contained within a fold in the rocks. The deeper you go, the more complex the folding, and the smaller the individual volumes. You have two technical challenges, leading to greatly increased costs—first, the targets are small, so they are difficult to “image” using geophysical techniques, and difficult to hit with a drill; and second, the reservoir is small, so there is not much economic benefit to offset the much higher costs (except by a much higher price).

Beyond this depth, you don’t have much chance of finding anything at all, as the temperature is too high to preserve the most valuable hydrocarbons.

Most of the data we have collected to date in the search for oil (and there are reams of it—I once heard that a major oil company was prepared to donate its entire collection of eastern Canada seismic data to the Geological Survey—just the tapes alone would fill a small building) are useless for looking for these deeper, smaller structures. It hurts to admit it, but there it is.

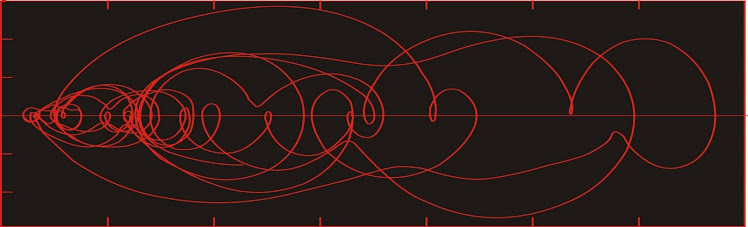

There is a small problem called spatial aliasing. You have a complex curve as in the figure. But your sampling is limited. How you sample is called CDP stacking. A series of shots are set off and the results recorded on geophones, and simply, all the reflections occur off one common point at depth, which is the sampled point. Then the entire array is dragged along some distance and repeated. But the smallest target that can be resolved is a function of your sampling interval. In particular, you need two samples to define a bend in the rocks (defining it accurately requires more).

If exploration geophysicists had unlimited budgets and placed no value on time, I have no doubt they would sample more frequently. But budgets are limited, and so geophysicists collect the minimum amount of data necessary to define their targets of interest, which over the past couple of decades have been that second layer of hydrocarbons in my cartoon of oil distribution. This data is not nearly dense enough to resolve the smaller targets on the third layer above.

What happens when you try to interpret geology without adequate data?

Oh yeah--you have to click on this figure for it to do anything.

Holy crap! Those hundred-million dollar holes that were supposed to be into a fat juicy anticline went into nothing! Not only are you fired and blacklisted from the industry, but you and your extended family are hereby sold into slavery.

So let’s leave aside oil for a moment.

What about metals? If we are nowhere near their peak production, why have their prices risen so sharply?

One reason may be inflation. More dollars chasing the metals.

There could be another—and that has to do with the fall of the price of metals (and most commodities) that began in the early 1970s. This fall had more to do with the rise of commodity futures trading than it did a sudden per capita increase in metals production. Many charts showed a drop in per capita production of basic commodities.

The per capita production of copper has risen through the 20th century, but four declines are apparent--WWI, the Depression, WWII, and the period from 1975 to 1985 or 90. Other commodity graphs appear similar. Was there an economic implosion equal to a Great Depression or a World War in that period?

When I was teaching early in the last decade, it was fashionable to look at such graphs and wonder if production for many of these metals was peaking.

The real reason for the drop in per capita production has to do with the fall in price. For producers, price is a signal. A rising price tells you to increase production. A falling price tells you to reduce production.

The problem comes from the paper pushers. If you have a certain amount of wealth, it seems intuitively obvious that if the price of what you have to buy falls, then you become wealthier. But this is only true if price falls due to an increase in supply.

If the price has fallen because of the ability of large corporate and banking interests to control the price downwards through the issuance of paper, then your wealth is not actually increasing.

After all, what is wealth? Isn’t wealth actually stuff—gold, oil, copper, grain, meat? If you drive the price down, but at the same time you have less stuff, then you have become poorer—for wealth is an abundance of oil, of gold, of food; but not of paper (or its electronic equivalents).

Creating all this paper has not made us richer! It has made us poorer!

Notice how per capita production of copper has increased over the past fifteen years. Do you feel richer? You should . . . except that much of that extra copper has gone to China, so unless you have been Chinese over that interval, you are not much wealthier (much like how the rapid growth from 1950 to 1975 was mainly experienced in North America).

We are a long way from the peak of everything (oil being the probable exception). We are currently in the process of revaluing real commodities in terms of paper. This revaluation is the equivalent of a complex system leaping from one metastable state to another. Huge volatility lies in our future, as corporate and banking interests, backed by huge government bailouts, double and redouble their efforts to regain control of commodity prices.

*The cheapest way to extract it may be to blow up the Earth. But there is an easy way to protect yourself. You simply buy land futures and take delivery after the Earth is destroyed!

Blogging by battery. Unfortunately I blew up the inverter last night.

Such things get me thinking about scarcity in general. The prices of many commodities have soared over the past two decades, particularly in the last ten years. What’s behind it?

Some have argued for “peak everything”.

Much has been written on the concept of peak oil. The idea here is that once we reach the point where we have produced about one-half of all oil in existence, oil production will decline. Some might argue we can keep production up awhile longer, but the idea is that as the amount remaining declines, eventually production must decline.

Hubbert said “We cannot produce what we have not discovered.”

The Earth is large, and for the most part we have barely scratched the surface. If the world were the size of a billiard ball, the depth to which we have plunged in search of resources would not even be visible. From my perspective as a geologist whose prime interest is in metals, we are nowhere near the peak ability to produce metals.

A paper published some years ago proposed the existence of a sphere of uranium (and other heavy metals) at the centre of the Earth, and some preliminary evidence that this sphere would have a radius of up to 6 km. Quite a lot of uranium, but I don’t care to hazard a guess as to the cost of its extraction*.

Oil, however, is a different matter. Given what we know of its formation, there cannot be substantial and increasing pools of accessible hydrocarbon at successively greater depths within the Earth beyond some level fairly close to the surface. Alternative theories of deep hot biospheres or primary hydrocarbon have extremely limited evidence in their favour, and in any case, the few molecules of hydrocarbon which may have been demonstrated to have drifted up through the basement geology from the deep Earth are but a small drop in the ocean of world demand. Oil is definitely a commodity which could be at or near its peak of production.

Having said that, I think we would find that at a price of about $1000/bbl (in constant 2010 dollars—no fair printing your way to this price!) we would still find a lot of oil at depth. But for geological reasons, this oil will be extremely expensive to discover and produce (hence the need for $1000/bbl).

The deeper the rocks are, the more tectonic episodes they have experienced. An oil reservoir is very simply the volume contained within a fold in the rocks. The deeper you go, the more complex the folding, and the smaller the individual volumes. You have two technical challenges, leading to greatly increased costs—first, the targets are small, so they are difficult to “image” using geophysical techniques, and difficult to hit with a drill; and second, the reservoir is small, so there is not much economic benefit to offset the much higher costs (except by a much higher price).

Beyond this depth, you don’t have much chance of finding anything at all, as the temperature is too high to preserve the most valuable hydrocarbons.

Most of the data we have collected to date in the search for oil (and there are reams of it—I once heard that a major oil company was prepared to donate its entire collection of eastern Canada seismic data to the Geological Survey—just the tapes alone would fill a small building) are useless for looking for these deeper, smaller structures. It hurts to admit it, but there it is.

There is a small problem called spatial aliasing. You have a complex curve as in the figure. But your sampling is limited. How you sample is called CDP stacking. A series of shots are set off and the results recorded on geophones, and simply, all the reflections occur off one common point at depth, which is the sampled point. Then the entire array is dragged along some distance and repeated. But the smallest target that can be resolved is a function of your sampling interval. In particular, you need two samples to define a bend in the rocks (defining it accurately requires more).

If exploration geophysicists had unlimited budgets and placed no value on time, I have no doubt they would sample more frequently. But budgets are limited, and so geophysicists collect the minimum amount of data necessary to define their targets of interest, which over the past couple of decades have been that second layer of hydrocarbons in my cartoon of oil distribution. This data is not nearly dense enough to resolve the smaller targets on the third layer above.

What happens when you try to interpret geology without adequate data?

Oh yeah--you have to click on this figure for it to do anything.

Holy crap! Those hundred-million dollar holes that were supposed to be into a fat juicy anticline went into nothing! Not only are you fired and blacklisted from the industry, but you and your extended family are hereby sold into slavery.

So let’s leave aside oil for a moment.

What about metals? If we are nowhere near their peak production, why have their prices risen so sharply?

One reason may be inflation. More dollars chasing the metals.

There could be another—and that has to do with the fall of the price of metals (and most commodities) that began in the early 1970s. This fall had more to do with the rise of commodity futures trading than it did a sudden per capita increase in metals production. Many charts showed a drop in per capita production of basic commodities.

Global copper production in tonnes per thousand population. Data compiled from

USGS and UN 2004 projections, digitized at five year intervals.

The per capita production of copper has risen through the 20th century, but four declines are apparent--WWI, the Depression, WWII, and the period from 1975 to 1985 or 90. Other commodity graphs appear similar. Was there an economic implosion equal to a Great Depression or a World War in that period?

When I was teaching early in the last decade, it was fashionable to look at such graphs and wonder if production for many of these metals was peaking.

The real reason for the drop in per capita production has to do with the fall in price. For producers, price is a signal. A rising price tells you to increase production. A falling price tells you to reduce production.

The problem comes from the paper pushers. If you have a certain amount of wealth, it seems intuitively obvious that if the price of what you have to buy falls, then you become wealthier. But this is only true if price falls due to an increase in supply.

If the price has fallen because of the ability of large corporate and banking interests to control the price downwards through the issuance of paper, then your wealth is not actually increasing.

After all, what is wealth? Isn’t wealth actually stuff—gold, oil, copper, grain, meat? If you drive the price down, but at the same time you have less stuff, then you have become poorer—for wealth is an abundance of oil, of gold, of food; but not of paper (or its electronic equivalents).

Creating all this paper has not made us richer! It has made us poorer!

Notice how per capita production of copper has increased over the past fifteen years. Do you feel richer? You should . . . except that much of that extra copper has gone to China, so unless you have been Chinese over that interval, you are not much wealthier (much like how the rapid growth from 1950 to 1975 was mainly experienced in North America).

We are a long way from the peak of everything (oil being the probable exception). We are currently in the process of revaluing real commodities in terms of paper. This revaluation is the equivalent of a complex system leaping from one metastable state to another. Huge volatility lies in our future, as corporate and banking interests, backed by huge government bailouts, double and redouble their efforts to regain control of commodity prices.

*The cheapest way to extract it may be to blow up the Earth. But there is an easy way to protect yourself. You simply buy land futures and take delivery after the Earth is destroyed!

so long and thanks for all the fish ;)

ReplyDelete