By modeling here I mean simulating some real system, whether it be physical, economic, or social. Not the other kind.

There are at least two sources of complexity which affect our ability to model a system.

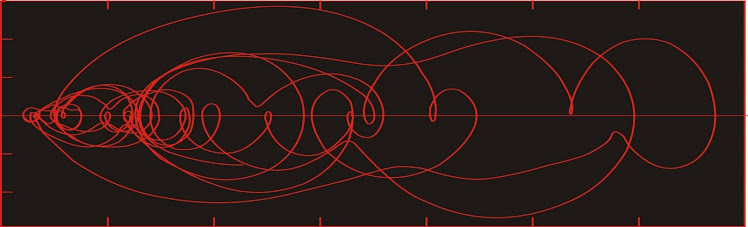

One is unforeseen complexity in the apparently simple mathematical relationships between variables in the system, usually arising from the nonlinear components (unpredictability arising when we use the right equation).

Another is the lack of understanding we have of how the individual elements in the system actually behave (unpredictability arising when we use the wrong equation).

I had a cousin who was working for TD at the time they were beginning to roll out their ATM system (they called them "Green Machines"). She described for me all of the testing procedures, whereby all the programmers tried to make every mistake they believed customers could possibly make. As problems arose, they fixed them.

The first question that the machine would ask a customer was "Do you have your green card?" and there were buttons for yes or no. If you didn't have a green card, you could use the keypad to enter your account information.

So they rolled out the machines, and on the very first day, a customer entered "no" when asked if he had a card, and then stuck his card in the slot. The entire system crashed. Apparently none of the programmers anticipated that.

Moral: the range of possible behaviours of the elements of a system is greater than can be anticipated.

Addition Sept. 13

On further reflection, the above story was actually about Canada Trust bank machines, not TD. They are the same company now, but were not at the time of the story.

There are at least two sources of complexity which affect our ability to model a system.

One is unforeseen complexity in the apparently simple mathematical relationships between variables in the system, usually arising from the nonlinear components (unpredictability arising when we use the right equation).

Another is the lack of understanding we have of how the individual elements in the system actually behave (unpredictability arising when we use the wrong equation).

I had a cousin who was working for TD at the time they were beginning to roll out their ATM system (they called them "Green Machines"). She described for me all of the testing procedures, whereby all the programmers tried to make every mistake they believed customers could possibly make. As problems arose, they fixed them.

The first question that the machine would ask a customer was "Do you have your green card?" and there were buttons for yes or no. If you didn't have a green card, you could use the keypad to enter your account information.

So they rolled out the machines, and on the very first day, a customer entered "no" when asked if he had a card, and then stuck his card in the slot. The entire system crashed. Apparently none of the programmers anticipated that.

Moral: the range of possible behaviours of the elements of a system is greater than can be anticipated.

Addition Sept. 13

On further reflection, the above story was actually about Canada Trust bank machines, not TD. They are the same company now, but were not at the time of the story.

No comments:

Post a Comment