This post is for those who still think that lower interest rates will lead to lower unemployment.

Information comes from Bureau of Labour Statistics and the Fred. Strangely, the historical data from the BLS does not match the data downloaded from the same site some months ago for previous posts on this topic--the differences are about 0.7% (i.e., the recent correction reduced the unemployment rate by 0.7% for December 2010).

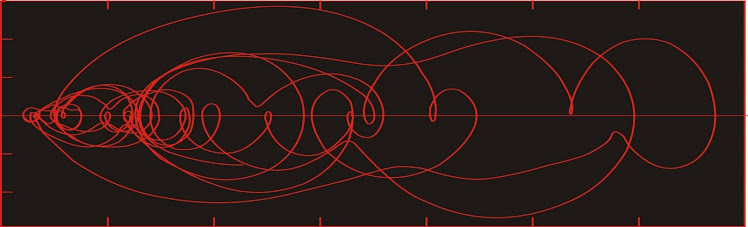

The scatterplot of real interest rates (which is calculated by subtracting the official inflation rate calculated from CPI data for all urban consumers including all items--annualized and smoothed through a 3-pt MA--from the 3-month treasury yield) against unemployment rate shows two distinct areas of Lyapunov stability in phase space. These are separated by a brief (four month) excursion into relatively high real interest rates. The lower-unemployment region of phase space is occupied from January 2001 until August 2008.

Notice that there is no discernable correlation between unemployment rate and interest rate. I recognize that this observation based on possibly manipulated data sets is at odds with the axioms of Keynesian economics and therefore should not be discussed.

The system experienced a bifurcation in late 2008. When real interest rates fell in late 2008, unemployment unexpectedly rose and the system settled into a new area of stability, where it has remained since.

The policy of frantically lowering interest rates has failed to bring down unemployment because of a fundamental change within the economic system. Continuing to hold interest rates low will not undo the irreversible change that occurred in 2008. It might be a good thing to spend some effort on understanding the dynamics of the economic system rather than continuing with actions based on axioms that are clearly at odds with the actual universe.

I recognize that the idea of the economic system undergoing fundamental changes to its dynamics is at odds with the axioms of Keynesian economics and therefore should not be discussed.

Feedback is a common feature of dynamic systems. In certain dynamic systems, there are areas of phase space where the system is dominated by negative feedback. Perturbations to the system are resisted. If the perturbation is large enough, however, the system may enter a state wherein positive feedbacks are dominant, in which case the system evolves rapidly through phase space until it arrives in (usually) a new area of phase space, where once again negative feedbacks dominate and the system regains some form of stability. These areas of stability are sometimes described as attractors, but for reasons discussed previously, we prefer to describe them as areas of Lyapunov stability.

A similar change is observed in the plot of unemployment duration vs real interest rates, once again covering the period from 2001 to present. Notice that the average duration of unemployment actually shows no correlation with real interest rates.

Observing the change is easy (if we disregard Keynesian axioms). Deducing the nature of the change is more difficult.

One observation that leaps out at me is this. Real interest rates fell to an extreme low in August 2005, followed by an extreme high in October 2006. They fill to an extreme low in June 2008, and rose to an extreme high in November 2008. In the first case, there were no dire effects on unemployment. But the second time around, we got a bifurcation.

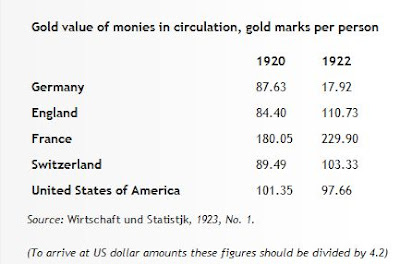

Is the answer here?

House prices were still rising in late 2005. They were falling in late 2008. Perhaps a fluctuation in interest rates when people believe they are becoming more wealthy is not harmful, but one that occurs during a time when our perception of wealth is falling led to a massive loss in confidence. Or at least a sudden realization that we couldn't afford all this debt.

If the change in economic dynamics is caused by a sudden negative perception of debt, then manipulating the interest rates downward will not and cannot bring us back to a paradise of low unemployment. Particularly if it is accompanied by declines in the Case-Schiller index and the stock market.

Information comes from Bureau of Labour Statistics and the Fred. Strangely, the historical data from the BLS does not match the data downloaded from the same site some months ago for previous posts on this topic--the differences are about 0.7% (i.e., the recent correction reduced the unemployment rate by 0.7% for December 2010).

The scatterplot of real interest rates (which is calculated by subtracting the official inflation rate calculated from CPI data for all urban consumers including all items--annualized and smoothed through a 3-pt MA--from the 3-month treasury yield) against unemployment rate shows two distinct areas of Lyapunov stability in phase space. These are separated by a brief (four month) excursion into relatively high real interest rates. The lower-unemployment region of phase space is occupied from January 2001 until August 2008.

Notice that there is no discernable correlation between unemployment rate and interest rate. I recognize that this observation based on possibly manipulated data sets is at odds with the axioms of Keynesian economics and therefore should not be discussed.

The system experienced a bifurcation in late 2008. When real interest rates fell in late 2008, unemployment unexpectedly rose and the system settled into a new area of stability, where it has remained since.

The policy of frantically lowering interest rates has failed to bring down unemployment because of a fundamental change within the economic system. Continuing to hold interest rates low will not undo the irreversible change that occurred in 2008. It might be a good thing to spend some effort on understanding the dynamics of the economic system rather than continuing with actions based on axioms that are clearly at odds with the actual universe.

I recognize that the idea of the economic system undergoing fundamental changes to its dynamics is at odds with the axioms of Keynesian economics and therefore should not be discussed.

Feedback is a common feature of dynamic systems. In certain dynamic systems, there are areas of phase space where the system is dominated by negative feedback. Perturbations to the system are resisted. If the perturbation is large enough, however, the system may enter a state wherein positive feedbacks are dominant, in which case the system evolves rapidly through phase space until it arrives in (usually) a new area of phase space, where once again negative feedbacks dominate and the system regains some form of stability. These areas of stability are sometimes described as attractors, but for reasons discussed previously, we prefer to describe them as areas of Lyapunov stability.

A similar change is observed in the plot of unemployment duration vs real interest rates, once again covering the period from 2001 to present. Notice that the average duration of unemployment actually shows no correlation with real interest rates.

Observing the change is easy (if we disregard Keynesian axioms). Deducing the nature of the change is more difficult.

One observation that leaps out at me is this. Real interest rates fell to an extreme low in August 2005, followed by an extreme high in October 2006. They fill to an extreme low in June 2008, and rose to an extreme high in November 2008. In the first case, there were no dire effects on unemployment. But the second time around, we got a bifurcation.

Is the answer here?

House prices were still rising in late 2005. They were falling in late 2008. Perhaps a fluctuation in interest rates when people believe they are becoming more wealthy is not harmful, but one that occurs during a time when our perception of wealth is falling led to a massive loss in confidence. Or at least a sudden realization that we couldn't afford all this debt.

If the change in economic dynamics is caused by a sudden negative perception of debt, then manipulating the interest rates downward will not and cannot bring us back to a paradise of low unemployment. Particularly if it is accompanied by declines in the Case-Schiller index and the stock market.