Some simple discussions today that follow from our last exciting episode.

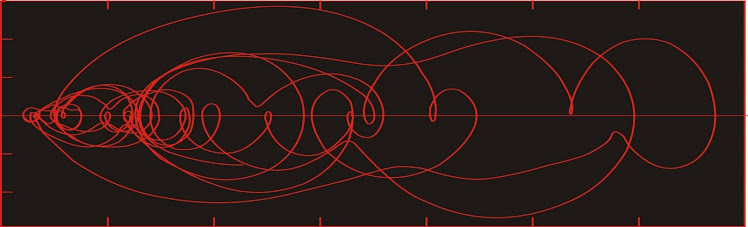

First issue - there is a limit to the size of deposits (given our current state of understanding). For gold, you can't have a hydrothermal flow system with a radius of hundreds of km--the crust is too thin. Also the crust has too many heterogeneities, which can each trap some amount of the gold in a circulating system. So at some point, the probability density for the right tail has to drop off a cliff, instead of declining steadily forever.

There are some interesting ideas about the Witwatersrand invoking means of forming gold deposits which are no longer active that could have formed deposits over scales of hundreds of km.

As an example, I have plotted the size distribution of reported deposits in Nevada (pdf here). It is a graph which should mimic the white hyperbola in the first figure. It might look better if we had a lot more deposits to work from. The smallest deposits on this chart were only about 2,000 ounces--and one of them had already been mined out. I would naturally expect far more accumulations of gold in that size range in Nevada--but for economic reasons, only two have had enough work done on them to define a resource.

Second point is that size isn't everything. There are quality issues to consider as well. For instance, conventional thinking suggests there is little appetite for financing mining operations on gold deposits smaller than 2 million ounces. Anecdotally, however, there is increasing interest in financing small, near-surface oxide deposits because their capex and operating costs are both low, recovery rates are high, and their long-term environmental legacy costs are likely to be low. Similarly, grade affects the economics in a more complex manner than we can capture in the above figures. What might work would be to classify the deposits by grade or type, and create the same type of plot--but that is a project for another day.

Third issue--obviously, the economics of the extraction business don't stay constant. There are technological breakthroughs, making extraction cheaper. Or the commodity price rises. These change the location of the left limb of our hyperbola, making a whole new group of deposits (generally among the smaller of them) economically attractive. But some large, hitherto uneconomic, deposits may become economic as well (I'm not going to name any names).

First issue - there is a limit to the size of deposits (given our current state of understanding). For gold, you can't have a hydrothermal flow system with a radius of hundreds of km--the crust is too thin. Also the crust has too many heterogeneities, which can each trap some amount of the gold in a circulating system. So at some point, the probability density for the right tail has to drop off a cliff, instead of declining steadily forever.

There are some interesting ideas about the Witwatersrand invoking means of forming gold deposits which are no longer active that could have formed deposits over scales of hundreds of km.

As an example, I have plotted the size distribution of reported deposits in Nevada (pdf here). It is a graph which should mimic the white hyperbola in the first figure. It might look better if we had a lot more deposits to work from. The smallest deposits on this chart were only about 2,000 ounces--and one of them had already been mined out. I would naturally expect far more accumulations of gold in that size range in Nevada--but for economic reasons, only two have had enough work done on them to define a resource.

Second point is that size isn't everything. There are quality issues to consider as well. For instance, conventional thinking suggests there is little appetite for financing mining operations on gold deposits smaller than 2 million ounces. Anecdotally, however, there is increasing interest in financing small, near-surface oxide deposits because their capex and operating costs are both low, recovery rates are high, and their long-term environmental legacy costs are likely to be low. Similarly, grade affects the economics in a more complex manner than we can capture in the above figures. What might work would be to classify the deposits by grade or type, and create the same type of plot--but that is a project for another day.

Third issue--obviously, the economics of the extraction business don't stay constant. There are technological breakthroughs, making extraction cheaper. Or the commodity price rises. These change the location of the left limb of our hyperbola, making a whole new group of deposits (generally among the smaller of them) economically attractive. But some large, hitherto uneconomic, deposits may become economic as well (I'm not going to name any names).