It is well known that industry money in support of research can corrupt the results. There have been a litany of stories in all aspects of scientific study from the pharmaceutical and food industries, to establishing liability from long-term use of hazardous industrial products to more recent allegations of tampering with the food pyramid. From the fight over aspartame as a sweetening agent to the latest pharmaceuticals, once significant amounts of money are involved there are frequently doubts as to the validity of the science.

For instance, at the GAC in Calgary in May, the session on Climate Change had a talk by one Mr. Norman Kalmanovitch concerning the impact on global warming of a doubling of atmospheric CO2. According to the paper, the effect would be negligible. The paper did cause something of a sensation, and there was a great deal of angry criticism directed at the speaker; unfortunately only a very limited amount of that criticism was directed at the science presented, and much more was directed at the funding sources of Mr. Kalmanovitch and their inferred ideological bent.

Now it may be true that Friends of Science is an ideologically driven organization, but that should not be the basis of criticism of the paper as presented. Unfortunately, it was nearly impossible to critique the presented paper as there were far too many slides (I believe he said there were 96, which I thought was a joke until he tried to go through them all). There was legitimate criticism about the length and confusion of the presentation, which cast doubt on the professionalism of the speaker and made it difficult to evaluate the science. I suggested to Mr. Kalmanovitch that he attempt to publish in peer-reviewed journals--at least then the ideas could be evaluated or criticized in an appropriate forum. Unfortunately, Mr. Kalmanovitch was of the opinion that the work would be rejected out of hand, as the climate journals were (in his opinion) ideologically driven organizations and he also felt that his own lack of academic stature would preclude any publication.

To the point--if a young researcher (just starting off in a tenure-track position at a Canadian university) found himself with an NSERC grant to study climate change, and obtained results through either observation or experimentation that falsified the global warming hypothesis, I submit that the announcement of said results would be a career-limiting move. Perhaps even a career-ending one.

There are a couple of issues here. One is that in many cases, the weight of corporate funds is designed to produce a scientific result in order to finesse an objective around government regulation. Without the high degree of government regulation around pharmaceuticals and food additives, it would not be necessary to obtain results favouring the project at any cost. And for those who ask whether we would be better off without government regulation--who is it that allowed Lipitor, aspartame, and other toxins to pollute our bodies. Has government regulation really kept toxins out of the food chain? Who has overseen the regulation of offshore? The stock market and the financial sector? Mortgage markets? Who was responsible for preventing Ponzi schemes like Madoff or Enron? We must ask ourselves--would we fire or would we promote an employee who allowed such mayhem into the various aspects of our lives? Why should we not do the same with the State? By continually increasing the funding for failure, we reward failure. We have rewarded failure to the point that society is now on the brink of destruction.

Yet those who are quick to decry the influence of corporate interests either deny or ignore scientific bias in favour of state goals. If it is true that corporate interests fund science that supports their aims, is it logical to suppose that governments would not do the same? Have not the massive bailouts of the financial industry against the expressed wishes of the general population made it clear that States do not act in the best interests of their populations? What about the murders of tens of millions in the last century?

The ongoing furor over leaked emails from climate research in England (dubbed "Climategate") may be the beginning of this realization. The widespread perception of a possible conflict of interest has poisoned public opinion and is emblamatic of widespread distrust of government-funded science.

Another problem with government grants is more subtle. The existence of grants tends to force research in directions which are more likely to attract grants. This is not necessarily a direction that research should go. One of the original models of academia held that research should be driven by curiosity. Now, however, curiosity isn't enough.

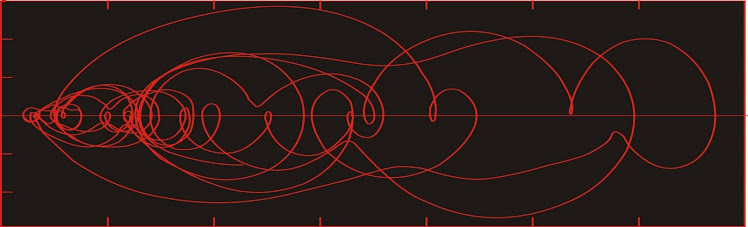

For example, I was once interviewed for a position at a well-known university in the UK. As in all such interviews, the question of future research topics came up. I had industry money arranged for investigating the environmental impact of offshore aggregate mining in the North Sea, but I had ideas for other projects as well. One of those was a continuation of my work on the dynamics of climate as determined from the geologic record. I wanted to pursue this as I saw what might be a short-lived lead in a field of endeavour that had great promise and could be done cheaply. Part of the promise was to deliver a methodology for testing climate models, and given the amount of money being spent on them, it seemed a good idea to evaluate them. Additionally, I knew that huge amounts of data were being collected at great expense, yet the methods of their analysis were primitive--and a small amount of money could greatly increase the value of what was being recovered at great expense. I was dismayed when the only question I received was how I would justify applying for a million-pound grant with such a project.

It was an aspect of research funding I had never really considered. Acquiring grant money for a young academic has always been necessary, but the amounts of money now being granted have attracted a new and unfortunate dynamic. The demand now is to design research projects which require large sums of money, which necessarily limits the types of proposals that can be formulated. For instance, in the field of paleoclimatology, the only types of projects that can justify grants of millions of dollars involve drilling holes somewhere remote (and crowd-pleasing). The resultant responsibility to ensure that the data obtained in such a project is thoroughly studied is ignored because of the need to obtain the next large grant (which usually involves more placing more holes somewhere else). Spending time contemplating the data obtained and attempting new methods of data processing in order to ensure that the best use is made of the data cannot compete with the drive to put new holes in distant places.

If you think that the funding agencies would be interested in granting relatively small amounts of money to improve the use of the data from these expensive boreholes, you would be mistaken. For they also have an interest in ensuring that large research grants are made. If you are overseeing the disbursement of $50 million, it is a lot easier to give out 25 $2 million grants than to give out a thousand $50 thousand grants. Your own salary is only dependent on doling out the money, so it makes sense to create as little work for yourself as possible.

Moving up the chain, we come to the politicians, whose interests in these matters are complex and contradictory. It can be a good thing to be sure that science is funded, but it would be bad if publicity came out that you were funding studies on the World of Warcraft, for instance. They would like to know that the money is being used effectively, but they do not have the scientific background to evaluate the science; so they place the responsibility in the hands of the funding agencies above.

I submit that the system works very differently from the way it was intended. I have no doubt that at every step, individuals acted in a way that they thought would lead to the best use of scientific resources. How do we explain how the result has come to be at odds with the intent?

(added July 28)

Gary North has written on the differences between a job and a calling. A job is what you do to make money. A calling is the highest, best use of your time. Your goal in life should be to do less job and more calling. If you are very lucky, your calling will be your job, but this is rare.

For most people in academia, teaching is their job, but their calling is research. Actually, the way they are funded, they probably view the research as both their job and their calling--the teaching is some condition of their obtaining research space, and is to be avoided.

My proposal for the financing of scientific research is as follows--let it fund itself!

Academic positions should essentially be teaching positions. If the academic wishes to research as well, that becomes a personal decision. University education is failing, at least in part because the system is geared to reward research, and if the academic is particularly good at research, teaching may even be avoided. Make teaching the main job of academics. Universities already carrying research equipment may use that to attract researchers who are would like to use it to further their research. Government should get out of funding research.

No comments:

Post a Comment